Practice with Two-Column Proofs

Practice with Two-Column Proofs

You may want to review:

- Practice with the Mathematical Words ‘and’, ‘or’, ‘is equivalent to’

- Introduction to the Two-Column Proof

In this section, you will practice with two-column proofs involving the Pythagorean Theorem, triangle congruence theorems, and other tools.

A couple lengthy proofs are explored. You can print worksheets for these proofs, and practice supplying reasons for each step yourself.

The first proof in this lesson involves an ‘averaging’ method called the geometric mean, which has important applications in (for example) biology and finance.

There are different types of ‘averaging’ methods in mathematics. Any type of ‘average’ is a way to replace a collection of numbers with a single number which, in some way, represents the collection. Different ‘averaging’ methods are appropriate in different situations.

The Geometric Mean

The first ‘average’ one usually encounters is the arithmetic mean: to find the arithmetic mean of $\,N\,$ numbers, add them up and then divide by $\,N\,.$

The geometric mean, on the other hand, involves multiplying and taking roots:

Let $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,$ be positive numbers.

The geometric mean of $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,$ is the positive number $\,\sqrt{ab}\,.$

Thus, to find the geometric mean of two positive numbers:

- multiply the numbers together

- take the square root of the result

Comments on the geometric mean

The definition extends to more than two numbers:

| To find the geometric mean of | three | positive numbers: | multiply them together; take the | cube root | of the result. |

| To find the geometric mean of | four | positive numbers: | multiply them together; take the | fourth root | of the result. |

| To find the geometric mean of | $\,n\,$ | positive numbers: | multiply them together; take the | $\,n^{\text{th}}\,$ root | of the result. |

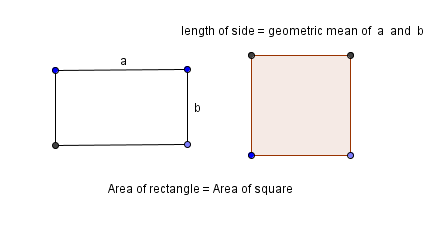

Take a rectangle with sides $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,.$ and re-shape it into a square, without changing the area. Then, the side length of the square is the geometric mean of $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,$:

$$ \begin{gather} \cssId{s48}{\text{area of rectangle is } ab}\cr\cr \cssId{s49}{\text{area of square is } (\sqrt{ab})(\sqrt{ab}) = ab} \end{gather} $$

There are equivalent ways to view the geometric mean. Here is the formulation that naturally appears in our first proof:

The geometric mean of $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,$ is the positive solution $\,g\,$ of the equation $\displaystyle\,\frac{a}{g} = \frac{g}{b}\,.$

The number $\,g\,$ is also referred to as the geometric mean between $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,.$

Note: Cross-multiplying $\,\frac{a}{g} = \frac{g}{b}\,$ gives $\,g^2 = ab\,,$ from which $\,g = \pm\sqrt{ab}\,.$ So, indeed, the positive solution is the geometric mean of $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,.$

The geometric mean tends to ‘dampen’ the effect of very large numbers. For example, the arithmetic mean of $\,10\,$ and $\,100,000\,$ is $\,\frac{10 + 100,000}{2} = 50,005\,.$ However, the geometric mean of $\,10\,$ and $\,100,000\,$ is only $\,\sqrt{(10)(100,000)} = 1000\,.$

This ‘dampening’ property makes the geometric mean particularly useful when working with collections of numbers that have greatly varying sizes. The reason this ‘dampening’ occurs is apparent from the next characterization; it will only be accessible to you if you've already studied logarithms and properties of logarithms.

The geometric mean of positive numbers $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,$ can be computed as follows:

- Average the base ten logarithms of the numbers: $$ \begin{align} &\cssId{s69}{y = \frac{\log_{10} a + \log_{10}b}2}\cr &\ \ \cssId{s70}{= \frac 12(\log_{10} ab)}\cr\cr &\ \ \cssId{s71}{= \log_{10} (ab)^{1/2}}\cr\cr &\ \ \cssId{s72}{= \log_{10}\sqrt{ab}} \end{align} $$

- Then, the geometric mean is obtained by ‘undoing’ this logarithmic average: $$ \begin{align} &\cssId{s74}{\text{geometric mean} = 10^y}\cr &\qquad\cssId{s75}{= 10^{\log_{10}\sqrt{ab}}}\cr &\qquad\cssId{s76}{= \sqrt{ab}} \end{align} $$

Proof #1: Right Triangles and the Geometric Mean

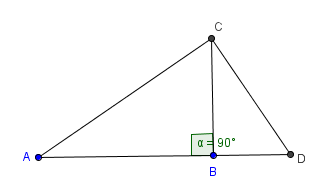

The geometric mean makes an interesting appearance in right triangles. If you drop an altitude from the right-angle vertex to the hypotenuse, the hypotenuse is thus split into two segments. The length of the altitude is the geometric mean between these two segments!

And, as the next proof shows, the converse is also true: if an altitude of a triangle is the geometric mean between the two segments of the side it hits, then the triangle must be a right triangle.

Sometimes, substitutions are a bit difficult to follow. Coloring is included in the beginning of the next proof to help you see what is being substituted for what.

A worksheet follows the proof; you can practice supplying reasons for each step.

GIVEN: $$\cssId{s92}{\overline{CB}\perp \overline{AD}}$$(That is, $\overline{CB}\,$ is an altitude of the triangle.) $$\cssId{s94}{\frac{AB}{BC} =\frac{BC}{BD}}$$ (That is, $\,BC\,$ is the geometric mean between $\,AB\,$ and $\,BD\,.$) PROVE: $\angle ACD\,$ is a right angle |

|

|

STRATEGY: Show that $\,(AC)^2 + (CD)^2 = (AB+BD)^2$ |

|

| PROOF: | |

| STATEMENTS | REASONS |

| 1. $\,\overline{CB} \perp \overline{AD}$ | given |

| 2. $\,\Delta ABC\,$ is a right triangle with hypotenuse $\,\overline{AC}\,$ | definitions: right triangle, hypotenuse |

| 3. $\,\color{red}{(AB)^2 + (BC)^2 = (AC)^2}$ | the Pythagorean Theorem |

| 4. $\,\Delta DBC\,$ is a right triangle with hypotenuse $\,\overline{CD}$ | definitions: right triangle, hypotenuse |

| 5. $\,\color{blue}{(BD)^2+ (BC)^2 = (CD)^2}$ | the Pythagorean Theorem |

|

6.

$

\begin{align}

&\color{red}{(AC)^2}

+

\color{blue}{(CD)^2}\cr

&\ \ \ =

\color{red}{(AB)^2 + (BC)^2}\cr

&\ \ \ \ \ \ \ +

\color{blue}{(BD)^2 + (BC)^2}

\end{align}

$

|

substitution (steps 3 and 5)

|

|

7.

$

\begin{align}

&(AC)^2+(CD)^2\cr

&\ \ =(AB)^2+2(BC)^2+(BD)^2

\end{align}

$

|

combine like terms |

| 8. $\displaystyle\,\frac{AB}{BC} =\frac{BC}{BD}$ | given |

| 9. $\,(AB)(BD)= (BC)^2$ | Multiplication Property of Equality; multiply both sides by $\,(BC)(BD)\,$ (i.e., cross-multiply) |

| 10. $\,2(AB)(BD)=2(BC)^2\,$ | Multiplication Property of Equality; multiply both sides by $\,2$ |

|

11.

$\begin{align}

&(AC)^2+(CD)^2\cr

&\ \ =(AB)^2+2(AB)(BD)+(BD)^2

\end{align}

$

|

substitution (steps 7 and 10) |

|

12.

$

\begin{align}

&(AB+BD)^2\cr

&\ \ =(AB)^2+2(AB)(BD)+(BD)^2

\end{align}

$

|

FOIL |

|

13.

$\begin{align}

&(AC)^2+(CD)^2\cr

&\ \ =(AB+BD)^2

\end{align}

$

|

substitution (steps 11 and 12) |

| 14. $\,AB+BD=AD$ | $\,B\,$ is between $\,A\,$ and $\,D\,$ |

| 15. $\,(AC)^2+(CD)^2=(AD)^2$ |

substitution (steps 13 and 14) |

| 16. $\,\Delta ACD\,$ is a right triangle with hypotenuse $\,\overline{AD}\,$; so, $\,\angle ACD\,$ is a right angle | the Pythagorean Theorem |

Click here to print a proof with a blank REASONS column, for practice:

Proof #2

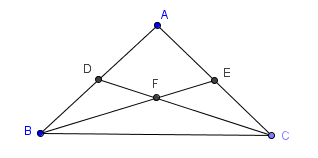

Here is a second proof, which gives you practice with some different tools. Again, you can create a worksheet with a blank ‘Reasons’ column, so you can supply the reasons yourself.

GIVEN:

$AB=AC$ PROVE: $DF=EF$ |

|

|

STRATEGY: Show that $\,\Delta BDF\cong \Delta CEF\,$ |

|

| PROOF: | |

| STATEMENTS | REASONS |

|

1.

$\,AB=AC\,$ $\,D\,$ is the midpoint of $\,\overline{AB}$ $\,E\,$ is the midpoint of $\,\overline{AC}$ |

given |

|

2.

$\,m\angle ACB= m\angle ABC\,$ |

angles opposite equal sides have equal measures |

| 3. $\,BD=\frac{1}{2}AB\,$ and $\,CE=\frac{1}{2}AC\,$ | definition of midpoint |

| 4. $\,BD=CE\,$ |

substitution (steps 1 and 3) |

| 5. $\,\overline{BC}\cong \overline{CB}$ | reflexive property (congruence is an equivalence relation on the set of geometric figures) |

| 6. $\,\Delta DBC\cong \Delta ECB$ | SAS (steps 2, 4, 5) |

| 7. $\,m\angle BCD =m\angle CBE\,$ | CPCTC |

| 8. $\,BF=CF\,$ | sides opposite equal measure angles are equal |

|

9.

$\begin{align}

&m\angle ABE + m\angle CBE\cr

&\ \ = m\angle ABC

\end{align}

$

and

$

\begin{align}

&m\angle ACD + m\angle BCD\cr

&\ \ = m\angle ACB

\end{align}

$

|

angle addition |

|

10.

$

\begin{align}

&m\angle ABE + m\angle BCD\cr

&\ \ = m\angle ACD + m\angle BCD

\end{align}

$

|

substitution (steps 2, 7, and 9)

|

| 11. $\,m\angle ABE = m\angle ACD$ | addition property of equality (subtract $\,m\angle BCD\,$ from both sides) |

|

12.

$\,\angle DFB\cong \angle EFC$ |

vertical angles are congruent |

|

13.

$\,\Delta BDF\cong \Delta CEF$ |

ASA (steps 8, 11, 12) |

|

14.

$\,DF=EF\,$ (or, $\,\overline{DF} \cong \overline{EF}$ ) |

CPCTC |

Click here to print a proof with a blank REASONS column, for practice:

In the exercises, you will also practice doing shorter two-column proofs; you will need to supply both the statements and reasons.

In your proofs, feel free to use statements like $\,\overline{AB}\cong \overline{CD}\,$ and $\,AB=CD\,$ totally interchangeably, since two segments are congruent if and only if they have the same length. However, be careful to use the verb ‘$\,\cong \,$’ to compare geometric figures, and the verb ‘$\,=\,$’ to compare numbers.

Similarly, feel free to use statements like $\,\angle ABC\cong \angle DEF\,$ and $\,m\angle ABC = m\angle DEF\,$ totally interchangeably, since two angles are congruent if and only if they have the same measure.