Multiplicity of Zeros and Graphical Consequences

Multiplicity of Zeros and Graphical Consequences

Recall that a zero of a function is an input whose corresponding output is zero.

For a real number $\,c\,,$ the following are equivalent:

- $c\,$ is a zero of $\,f\,$

- $\,f(c) = 0\,$

- the point $\,(c,0)\,$ lies on the graph of $\,f\,$

- the graph of $\,f\,$ crosses the $\,x\,$-axis at $\,c\,$

- the number $\,c\,$ is an $x$-intercept for the graph of $\,f$

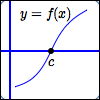

$c\,$ is a zero of $\,f$

$c\,$ is a zero of $\,f$

Need help with this ‘function box’ sketch?

Take a few minutes to skim

function notation.

Graph of $\,f\,$ crosses the

$x$-axis at $\,c$

Graph of $\,f\,$ crosses the

$x$-axis at $\,c$

For a particular type of function—a polynomial—we can say even more. For a polynomial, there is a beautiful relationship between the zeroes and the factors.

For a polynomial $\,P\,$ and a real number $\,c\,,$ the following are equivalent:

- $c\,$ is a zero of $\,P\,$

- $x - c\,$ is a factor of $\,P(x)\,$

Having said this, though, a study of the chart below will show that:

The zeros alone don't give the full richness of information that we might want and need.

All the functions below have the same zero: $\,x = 1\,.$ All the functions below have graphs that cross the $x$-axis at the same place: $\,x = 1\,.$

But, the functions behave very differently near $\,1\,,$ and we need a way to easily talk about this difference. ‘Multiplicity’ to the rescue!

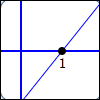

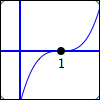

Exactly one factor of $\,x - 1\,$:

$$\cssId{s24}{y = (x - 1)^{\color{red}{1}} = x - 1}$$$1\,$ is a zero of multiplicity $\,\color{red}{1}$

That is, $\,1\,$ is a simple zero.

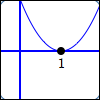

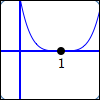

Two factors of $\,x - 1\,$:

$$\cssId{s28}{y = (x - 1)^{\color{red}{2}}}$$$1\,$ is a zero of multiplicity $\,\color{red}{2}$

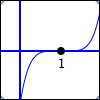

Three factors of $\,x - 1\,$:

$$\cssId{s31}{y = (x - 1)^{\color{red}{3}}}$$$1\,$ is a zero of multiplicity $\,\color{red}{3}$

Four factors of $\,x - 1\,$:

$$\cssId{s34}{y = (x - 1)^{\color{red}{4}}}$$$1\,$ is a zero of multiplicity $\,\color{red}{4}$

Five factors of $\,x - 1\,$:

$$\cssId{s37}{y = (x - 1)^{\color{red}{5}}}$$$1\,$ is a zero of multiplicity $\,\color{red}{5}$

Let $\,P\,$ be a polynomial, and let $\,k\,$ be a positive integer.

The following are equivalent:

- $\,c\,$ is a zero of multiplicity $\,k\,$

- $\,x-c\,$ is a factor of $\,P(x)\,$ exactly $\,k\,$ times

A zero of multiplicity $\,1\,$ is called a simple zero.

Example: Multiplicity of Zeroes

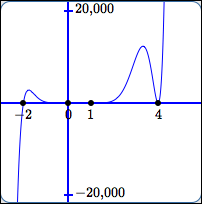

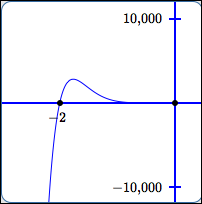

Let: $$P(x) = (x+2)x^5(x-1)^3(x-4)^2$$

Then:

It is impossible to get a single to-scale graph of $\,P\,$ that clearly shows the interesting behavior near all the zeroes. (The next section discusses this in more detail.)

Study the graphs below, paying close attention to the scales on the $\,x\,$ and $y$-axes:

simple zero

Behavior at the zero:

graph cuts straight through

(no flattening)

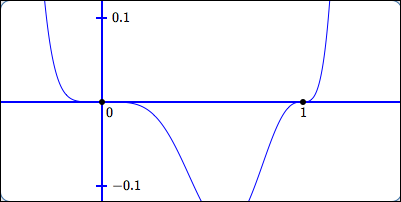

zeros of odd multiplicity greater than $1$

Behavior at the zeroes:

horizontal tangent lines;

sign changes;

the higher the multiplicity,

the more flattening

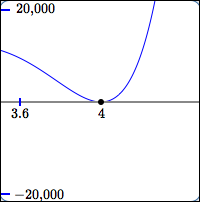

zero of even multiplicity

Behavior at the zero:

horizontal tangent line;

no sign change

Example

Let: $$P(x) = -\frac 35(3x - 5)^7(-x)^4(8 - x)^3$$

List the zeros of $\,P\,,$ together with their multiplicities.

Solution: Since $$ \begin{align} &\cssId{s83}{(3x-5)^7}\cr &\quad \cssId{s84}{= [ 3(x - \frac{5}{3}) ]^7}\cr &\quad \cssId{s85}{= 3^7(x - \frac{5}{3})^7} \end{align} $$ the zero $\,\frac{5}{3}\,$ has multiplicity $\,7\,.$ You don't need to go through all this work: just solve $\,3x - 5 = 0\,$ to get the zero; assign the power as the multiplicity.

Since $$\,(-x)^4 = (-1)^4x^4 = x^4$$

the zero $\,0\,$ has multiplicity $\,4\,.$ Here's the shortcut: solve ‘$\,-x = 0\,$’ to get the zero; assign the power as the multiplicity.

Since $$ \begin{align} &\cssId{s96}{(8 - x)^3}\cr &\quad \cssId{s97}{= [-1(x - 8)]^3}\cr &\quad \cssId{s98}{= (-1)^3(x-8)^3} \end{align} $$ the zero $\,8\,$ has multiplicity $\,3\,.$ The shortcut: solve ‘$\,8 - x = 0\,$’ to get the zero; assign the power as the multiplicity.

| zero | multiplicity |

| $\frac{5}{3}$ | $7$ |

| $0$ | $4$ |

| $8$ | $3$ |

Multiplicity of Zeroes: Graphical Consequences

| Multiplicity of zero: | Multiplicity $\,1\,$: a simple zero | ||

| Sign change at zero? | Yes | ||

| Horizontal tangent line at zero? | No | ||

| Flattening behavior at zero: | No flattening; graph cuts straight through | ||

Sample graphs:

|

|||

| Multiplicity of zero: | Even multiplicities $2$, $4$, $6$, $\ldots$ | |||||||||

| Sign change at zero? | No | |||||||||

| Horizontal tangent line at zero? | Yes | |||||||||

| Flattening behavior at zero: | More flattening as multiplicity increases | |||||||||

Sample graphs:

|

||||||||||

| Multiplicity of zero: | Odd multiplicities $3$, $5$, $7$, $\ldots$ | |||||||||

| Sign change at zero? | Yes | |||||||||

| Horizontal tangent line at zero? | Yes | |||||||||

| Flattening behavior at zero: | More flattening as multiplicity increases | |||||||||

Sample graphs:

|

||||||||||

Why the Sign Change for Odd Multiplicities, But Not Even?

Suppose that $\,c\,$ is a zero of a polynomial, so there is an $x$-intercept at $\,c\,.$

Suppose you want to figure out if the sign of the polynomial changes (or not) as you pass through $\,c\,.$

Maybe it does change sign at $\,c\,$: perhaps it is negative on the left (graph below the $x$-axis) and positive on the right (graph above the $x$-axis).

Or, maybe it doesn't change sign at $\,c\,$: perhaps it is negative both to the left and right of $\,c\,.$

Here's the good news:

To figure out if the sign (plus or minus) of the polynomial changes as you pass through $\,c\,,$ all you have to do is investigate the $\,x-c\,$ factor(s).

Why is this? The idea is illustrated with an example.

Consider the same polynomial as above: $$\cssId{s147}{P(x) = (x+2)x^5(x-1)^3(x-4)^2}$$ Let's decide if there's a sign change at $\,x = 1\,.$

Write the function as: $$\cssId{s150}{P(x) = (x-1)^3\ \cdot\ } \cssId{s151}{\overbrace{x^5(x+2)(x-4)^2}^{\text{stuff}}}$$ Notice that all the factors of $\,(x-1)\,$ have been pulled out to the front, and the remaining factors have been labeled ‘stuff ’.

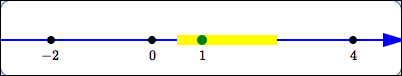

The number line below shows all the zeroes of $\,P\,.$ Recall that zeroes are the only type of place where a polynomial can change its sign, since there are no breaks in its graph.

The interval highlighted in yellow doesn't contain any zero except the one under consideration. Since a polynomial has a finite number of zeroes, you can always get such an interval. For example, you can always go halfway to the closest zero on the left, and halfway to the closest zero on the right, as was done here.

Inside the yellow interval, ‘stuff ’ has a constant sign:

- $x = x - 0$ is positive, since every number in the yellow interval is to the right of zero

- $x + 2 = x - (-2)$ is positive, since every number in the yellow interval is to the right of $-2$

- $x - 4$ is negative, since every number in the yellow interval is to the left of $4$

- So: $$ \begin{align} &\cssId{s168}{x^5(x+2)(x-4)^2}\cr &\qquad \cssId{s169}{= (+)^5(+)(-)^2}\cr &\qquad \cssId{s170}{= (+)(+)(+)}\cr &\qquad \cssId{s171}{= (+)} \end{align} $$

Since ‘stuff ’ doesn't change its sign inside the yellow interval, the only part of the formula that affects the sign of $\,P(x)\,$ in the yellow interval is $\,(x-1)^3\,.$

- To the left of $\,1\,,$ $\,(x-1)^3\,$ is negative.

- To the right of $\,1\,,$ $\,(x-1)^3\,$ is positive.

So, $\,P(x)\,$ does change sign at $\,1\,.$

Let $\,P(x)\,$ be a factored polynomial.

Then:

- For factors of the form $\,(x-c)^{\text{ODD}}\,,$ $\,P(x)\,$ does change its sign at $\,c\,.$

- For factors of the form $\,(x-c)^{\text{EVEN}}\,,$ $\,P(x)\,$ does not change its sign at $\,c\,.$

Example

Let: $$ \begin{align} &P(x)\cr &\ = -11(x+7)^5(x+3)^8(x+1)(x^4)(x - 5)^2(x - 8)^3 \end{align} $$

The zeroes of $\,P\,$ are: $$\cssId{s187}{-7,\ -3,\ -1,\ 0,\ 5,\ 8}$$

The function $\,P\,$ changes its sign at $\,-7\,,$ $\,-1\,,$ and $\,8\,,$ since the corresponding factors are raised to odd powers.

The function $\,P\,$ does not change its sign at $\,-3\,,$ $\,0\,,$ and $\,5\,,$ since the corresponding factors are raised to even powers.

Why do the Graphs ‘Flatten Out’ as the Multiplicity Gets Higher?

A small number (between $\,-1\,$ and $\,1\,$), when multiplied by itself, gets even smaller (closer to zero).

The number $\,x - c\,$ is small when $\,x\,$ is close to $\,c\,.$ So, when $\,x - c\,$ gets repeatedly multiplied by itself, it gets smaller, and smaller, and smaller.

Look at the numbers and graphs below. For higher multiplicities, the outputs are smaller, so the points are closer to the $x$-axis!

| $x$ |

| $3.1$ |

| All these graphs have the same horizontal and vertical scales. |

| $(x - 3)$ |

| $0.1$ |

$y = x - 3$ point $(3.1\,,\,0.1)$ |

| $(x - 3)^2$ |

| $0.01$ |

$y = (x - 3)^2$ point $(3.1\,,\,0.01)$ |

| $(x - 3)^3$ |

| $0.001$ |

$y = (x - 3)^3$ point $(3.1\,,\,0.001)$ |

| $(x - 3)^4$ |

| $0.0001$ |

$y = (x - 3)^4$ point $(3.1\,,\,0.0001)$ |

| $(x - 3)^5$ |

| $0.00001$ |

$y = (x - 3)^5$ point $(3.1\,,\,0.00001)$ |