Vectors: From Horizontal/Vertical Components to Direction/Magnitude

Vectors: From Horizontal/Vertical Components to Direction/Magnitude

You may want to review prior sections:

- Introduction to Vectors

- Working With the Arrow Representation for Vectors

- Working With the Analytic Representation for Vectors

- Unit Vectors

- Formula For the Length of a Vector

- Vectors: From Direction/Magnitude to Horizontal/ertical components

Let $\,\overrightarrow{v}\,$ be a vector with known analytic form $\,\langle a\,,\,b\rangle\,$:

- The horizontal component is $\,a$

- The vertical component is $\,b$

Throughout this section, $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,$ are real numbers.

How can this information be used to find the direction and magnitude of the vector $\,\overrightarrow{v}\,$? In other words, given the horizontal and vertical components of a vector, what are its magnitude and direction?

Getting Magnitude (Size, Length) From Horizontal and Vertical Components

As shown in an earlier section, the magnitude of $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle a\,,\,b\rangle\,$ is:

$$ \cssId{s9}{ \|\overrightarrow{v}\| = \sqrt{\strut a^2 + b^2}} $$In words: the magnitude of a vector is the square root of the sum of the squares of its components.

Magnitude: The Zero Vector

The zero vector is $\,\langle 0\,,\,0\rangle\,.$

- If $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle 0\,,\,0\rangle\,,$ then $\,\|\overrightarrow{v}\| = \sqrt{0^2 + 0^2} = 0\,.$ The zero vector has magnitude zero.

- If $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle a\,,\,b\rangle\,$ is a vector with $\,\|\overrightarrow{v}\| = 0\,,$ then $\,\sqrt{a^2 + b^2} = 0\,.$ The only way this can happen is for both $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,$ to equal zero. Thus, $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle 0\,,\,0\rangle\,.$ If a vector has magnitude zero, then it must be the zero vector.

-

Putting both directions together:

$\|\overrightarrow{v}\| = 0\,$ if and only if $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle 0\,,\,0\rangle\,$

Getting (Standard) Direction from Horizontal and Vertical Components

The direction of a vector can be described in different ways. For example, bearings are often used in navigation.

The angle conventions used to define the trigonometric functions give a particularly convenient way to define the direction of a vector. For the reader's convenience, this scheme is repeated below:

‘Standard Direction’ Angle Conventions

Place the tail of the vector at the origin of a rectangular coordinate system.

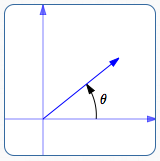

Indicate the vector's direction using an angle $\,\theta\,$ laid off as follows:

- Start at the positive $x$-axis

- Positive angles are swept out in a counterclockwise direction (start by going up)

- Negative angles are swept out in a clockwise direction (start by going down)

When it's necessary to emphasize that this direction scheme is being used, it will be referred to as the standard direction.

Standard direction is not unique. For example, $\,\theta = 30^\circ\,$ and $\,\theta = -330^\circ\,$ both describe a vector pointing the same way. In what follows, the symbol $\,\theta\,$ (theta) always refers to standard direction, and simple values of $\,\theta\,$ are used.

a positive angle $\,\theta$

a negative angle $\,\theta$

Standard Direction for Vectors Pointing Up/Down/Left/Right

When at least one component (horizontal or vertical) of a vector equals zero, then no formula is needed to find standard direction. Here's a table that summarizes the results for $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle a\,,\, b\rangle\,$:

| Horizontal |

Arrow Representation | Standard Direction, $\,\theta$ |

|

the zero vector: $a = 0\,$ and $\,b = 0$ |

(no arrow representation) | the zero vector has no direction; the direction of $\,\langle 0,0\rangle\,$ is undefined |

| $\overrightarrow{v} = \langle a\,,\,0\rangle\,$ with $\,a \gt 0$ |

vector points to the right |

$\theta = 0^\circ$ |

| $\overrightarrow{v} = \langle a\,,\,0\rangle\,$ with $\,a \lt 0\,$ |

vector points to the left |

$\theta = 180^\circ$ |

| $\overrightarrow{v} = \langle 0\,,\,b\rangle\,$ with $\,b \gt 0$ |

vector points up |

$\theta = 90^\circ$ |

| $\overrightarrow{v} = \langle 0\,,\,b\rangle\,$ with $\,b \lt 0$ |

vector points down |

$\theta = 270^\circ\,$ or $\,\theta = -90^\circ$ |

Formula For Standard Direction for Vectors in Quadrants I and IV

For an arbitrary vector, the arctangent function gives convenient formulas for standard direction. However, different formulas are needed in different quadrants.

Why are different formulas needed? The arctangent only gives angles between $\,-90^\circ\,$ and $\,90^\circ\,,$ so (without adjustment) it can only cover vectors in quadrants IV and I. Keep reading!

Recall that, by definition:

This is the ‘degree version’ of the definition. Remember:

- If your calculator is in degree mode, $\,\arctan x\,$ will be in degrees

- If your calculator is in radian mode, $\,\arctan x\,$ will be in radians

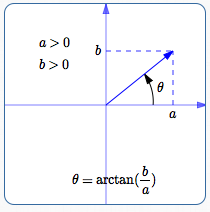

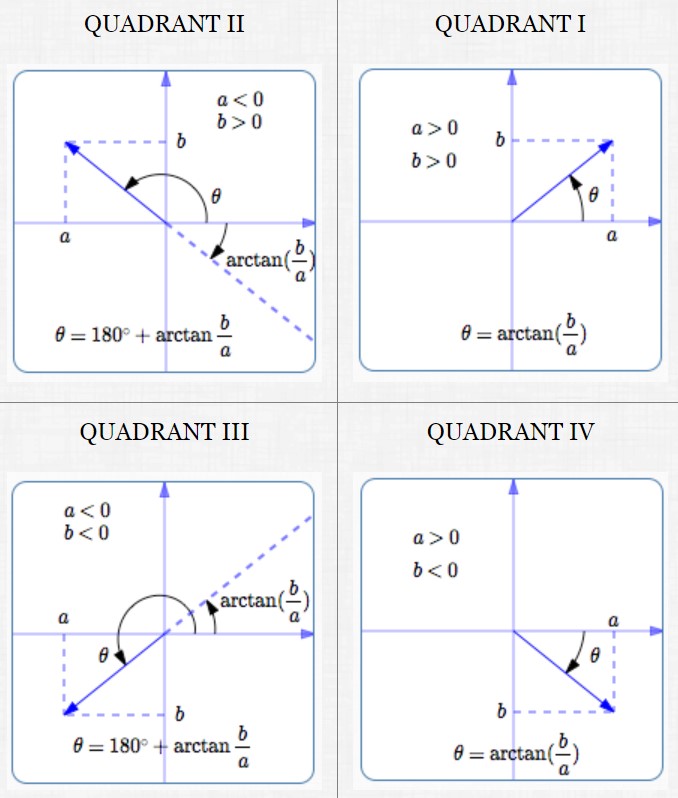

Quadrant I

In Quadrant I, where $\,a \gt 0\,$ and $\,b \gt 0\,,$ everything is simple: $$ \begin{gather} \cssId{s83}{\tan\theta = \frac ba}\cr\cr \cssId{s84}{\theta = \arctan\bigl(\frac ba\bigr)} \end{gather} $$

When $\,\frac ba\,$ is positive, $\,\arctan(\frac ba)\,$ returns the angle between $\,0^\circ\,$ and $\,90^\circ\,$ whose tangent is $\,\frac ba\,.$ This is just the angle we want!

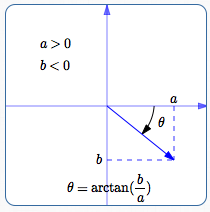

Quadrant IV

Things are similarly easy in quadrant IV. Here, $\,\frac ba\,$ is negative, and $\,\arctan(\frac ba)\,$ returns an angle between $\,-90^\circ\,$ and $\,0^\circ\,.$ Again, this angle provides a correct direction for the vector.

If you want a positive angle for the direction (instead of the negative one provided by the arctangent), you can use the formula $\,360^\circ + \arctan(\frac ba) \,.$

In summary:

This formula always yields an angle between $\,0^\circ\,$ and $\,90^\circ\,.$

This formula always yields an angle between $\,-90^\circ\,$ and $\,0^\circ\,.$

OR

In Quadrant IV:

$$\cssId{s103}{\theta = 360^\circ + \arctan(\frac ba)}$$This formula always yields an angle between $\,270^\circ\,$ and $\,360^\circ\,.$

Summary: Standard Direction of $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle a,b\rangle\,$ in All Four Quadrants

The formula for the (standard) direction of a vector $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle a\,,\,b\rangle\,$ depends upon the signs of $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,,$ as indicated below:

Formula for Standard Direction for Vectors in Quadrants II and III

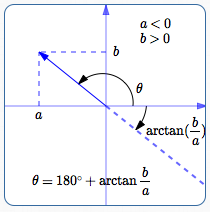

Quadrant II

In Quadrant II, where $\,a \lt 0\,$ and $\,b \gt 0\,,$ we have to be careful.

In Quadrant II, we want a direction angle $\,\theta\,$ between $\,90^\circ\,$ and $\,180^\circ\,.$

In Quadrant II, $\,\frac ba\,$ is negative, so $\,\arctan(\frac ba)\,$ returns an angle between $\,-90^\circ\,$ and $\,0^\circ\,.$

In Quadrant II, these are different angles:

- The (desired, positive) direction angle: $\,\theta$

- The (undesired, negative) angle: $\,\arctan(\frac ba)$

Note that both of these angles have tangent value equal to $\,\frac ba\,.$

To get from $\,\arctan(\frac ba)\,$ to $\,\theta\,,$ just add $\,180^\circ\,.$

This formula always yields an angle between $\,90^\circ\,$ and $\,180^\circ\,.$

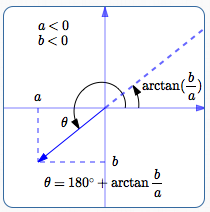

Quadrant III

In Quadrant III, where $\,a \lt 0\,$ and $\,b \lt 0\,,$ we also have to be careful.

In Quadrant III, we want a direction angle $\,\theta\,$ between $\,180^\circ\,$ and $\,270^\circ\,.$

In Quadrant III, $\,\frac ba\,$ is positive, so $\,\arctan(\frac ba)\,$ returns an angle between $\,0^\circ\,$ and $\,90^\circ\,.$

In Quadrant III, these are different angles:

- The (desired) direction angle: $\,\theta$

- The (undesired) angle: $\,\arctan(\frac ba)$

Note that both of these angles have tangent value equal to $\,\frac ba\,.$

To get from $\,\arctan(\frac ba)\,$ to $\,\theta\,,$ just add $\,180^\circ\,.$

This formula always yields an angle between $\,180^\circ\,$ and $\,270^\circ\,.$

The ‘Reference Angle’ Method for Finding (Standard) Direction

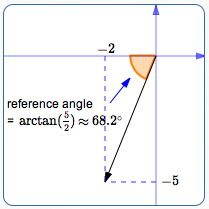

Instead of using the formulas for direction discussed above, you can always find the reference angle for the vector, and then adjust. The reference angle is the acute angle between the vector and the $x$-axis.

Example

Find the standard direction of $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle -2\,,\,-5\rangle\,.$ Report as a positive angle in the interval $\,[0^\circ,360^\circ)\,.$

Solution

Initially ignore the signs (plus/minus) of the horizontal and vertical components of $\,\overrightarrow{v} = \langle a\,,b\rangle\,.$

Find $\displaystyle\,\arctan\frac{|b|}{|a|}\,.$ This is always a positive, acute angle.

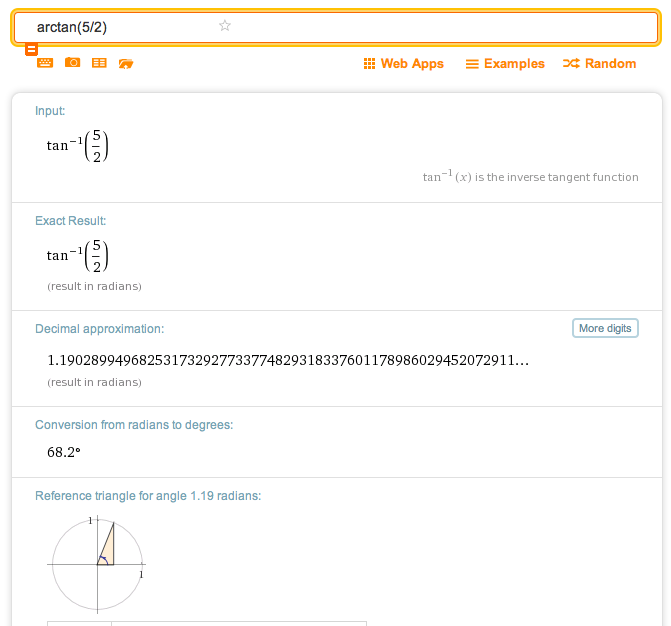

Here, $\,\arctan \frac{|-5|}{|-2|} = \arctan\frac 52 \approx 68.2^\circ\,.$

Adjust as needed to get standard direction. In this example, you'll add $\,180^\circ\,$:

Standard direction $\,= 68.2^\circ + 180^\circ = 248.2^\circ$

Using WolframAlpha to Find Arctangent

You can use WolframAlpha to find the arctangent: