‘Trapping’ the Roots of a Polynomial: An Interval Guaranteed to Contain All Real Roots

(This lesson is optional in the Precalculus course.)

It's often helpful to have an interval that is guaranteed to hold all the real roots of a polynomial.

This section states and proves such a theorem. It's a beautiful proof, which uses some important properties of the real numbers that have not yet appeared in this course.

In particular, if you're using a calculator to graph a polynomial, then you probably want to set your window so you're guaranteed to see all the $x$-intercepts. This section is for you!

Here's the outline for this section:

- The ‘Bounding the Real Roots of a Polynomial’ Theorem

- Examples—How to Use the Theorem

- Tools Needed to Prove the Theorem

- A Detailed and Careful Proof

an interval guaranteed to contain all real roots

Let $\,P\,$ be a polynomial of degree $\,n\ge 1\,$ with real coefficients. That is, $$\cssId{s17}{P(x) = a_nx^n + a_{n-1}x^{n-1} + \cdots + a_1x + a_0}$$ where $\,a_n\ne 0\,$ and all the $\,a_i\,$ are real numbers.

Let: $$M := \text{max}\bigl(\,|a_{n-1}|,\ldots,|a_0|\,\bigr)$$

Let $\,r\,$ be any real root (zero) of $\,P\,,$ so that $\,P(r) = 0\ $.

Then:

$$\cssId{s22}{|r| \le 1 + \frac{M}{|a_n|}}$$If we define $$K := 1 + \frac{M}{|a_n|}$$ then

All the real zeros of $\,P\,$ are contained in the interval $\,[-K,K]\,.$

Notes on the Theorem

- Recall that ‘:=’ means ‘equals, by definition’.

- To find $\,M\,$: look at all the coefficients except the leading coefficient, and choose the one with the biggest absolute value. Then, $\,M\,$ is the absolute value of this chosen coefficient.

For More Advanced Readers

You may want to compare the theorem and proof on this page with Cauchy's Bound for the Roots of a Polynomial.

The theorem and proof given on this page (the page you're currently reading) actually provides a bound for all complex roots of a polynomial. In this case, $\,K\,$ is the radius of a bounding circle centered at the origin in the complex plane.

For a complex number $\,z := a + bi\,,$ $\,|z|\,$ is called the modulus of $\,z\,$:

$$ \begin{align} &\cssId{s35}{|z|}\cr &\quad \cssId{s36}{=\ |a + bi|}\cr &\quad\cssId{s37}{=\ \text{distance of $\,z\,$ from the origin in the complex plane}}\cr &\quad \cssId{s38}{=\ \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}} \end{align} $$The theorem and proof given on this page (the page you're currently reading) actually works when the polynomial coefficients $\,a_i\,$ are complex numbers.

Examples: How to Use the Theorem

Example 1

Let: $$\begin{align} P(x) &= (x-1)(x+2)(x-3)\cr &= x^3 - 2x^2 - 5x + 6 \end{align} $$

It's clear from the factored form that the roots of $\,P\,$ are $\,1\,,$ $\,-2\,,$ and $\,3\,,$ so we'll be able to confirm the bounding interval obtained from the theorem.

- $n\,$ (the degree) is $3$

- $a_3\,$ (the leading coefficient) is $\,1\,$

- $M = \text{max}\bigl(\,|-2|\,,\,|-5|\,,\,|6|\,\bigr) = 6$

- $\displaystyle K \ =\ 1 + \frac{M}{|a_n|} \ =\ 1 + \frac{6}{|1|} \ =\ 1 + 6 = 7$

- All the zeroes are guaranteed to lie in the interval $\,[-K,K] = [-7,7]\,$ (which they do!)

- Notice that the theorem does not necessarily give a tight bound on the zeros!

Example 2

The previous example is tweaked by changing the leading coefficient to $\,7\,.$

Let: $$P(x) = 7x^3 - 2x^2 - 5x + 6$$

- $n\,$ (the degree) is $3$

- $a_3\,$ (the leading coefficient) is $\,7\,$

- $M = \text{max}\bigl(\,|-2|\,,\,|-5|\,,\,|6|\,\bigr) = 6$

- $\displaystyle K \ =\ 1 + \frac{M}{|a_n|} \ =\ 1 + \frac{6}{|7|} \ =\ \frac{13}{7}\ \approx\ 1.9$

- All the zeroes are guaranteed to lie in the interval $\,[-\frac{13}{7},\frac{13}{7}]\,.$

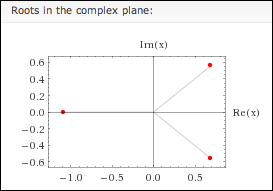

A quick trip to WolframAlpha shows that there is only one real root, which is approximately $\,-1.1\,.$

Here's a sketch from WolframAlpha that shows all the complex roots:

Tools Needed to Prove the Theorem

(1) The Triangle Inequality

For all real numbers $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,$:

$$\cssId{s63}{|a+b| \le |a| + |b|}$$(The Triangle Inequality is proved in problem type #4 below.)

(2) Properties of Absolute Value

For all real numbers $\,a\,$ and $\,b\,$:

- $|ab| = |a|\cdot|b|$

- $\displaystyle \left|\frac{a}{b}\right| = \frac{|a|}{|b|}$ ($b\ne 0$)

(3) Properties (1) and (2) Extend to Finite Sums/Products

For example:

$$ \begin{align} |a + b + c| &\le |a| + |b + c|\cr\cr &\le |a| + |b| + |c| \end{align} $$

and

$$ \begin{align} |abc| &= |a|\cdot|bc|\cr\cr &= |a|\cdot|b|\cdot|c| \end{align} $$

In particular: $|x^n| = |x|^n\,.$

(4) Properties (1) and (2) also hold for complex numbers, where $\,|\cdot|\,$ is the modulus of a complex number

Complex numbers are explored in the next few sections.

(5) Sum of a Finite Geometric Series

For all real numbers $\,a\,$ and for $\,x \ne 1\,$:

$$ \cssId{s81}{a + ax + ax^2 + \cdots + ax^n = \frac{a(x^{n+1}-1)}{x-1}} $$(There is lots of practice with geometric series in problem types #9, #10, and #11 below.)

Proof of the ‘Bounding the Real Roots of a Polynomial’ Theorem

Let $\,r\,$ be a real root of $\,P\,,$ so $\,P(r) = 0\ $:

$$a_nr^n + a_{n-1}r^{n-1} + \cdots + a_1r + a_0 = 0$$Dividing both sides of the equation by $\,a_n\ne 0\,$ gives the equivalent equation:

$$r^n + \frac{a_{n-1}}{a_n}r^{n-1} + \cdots + \frac{a_1}{a_n}r + \frac{a_0}{a_n} = 0 \tag{1}$$Define $$M := \text{max}\bigl(\,|a_{n-1}|,\ldots,|a_0|\,\bigr)\,,$$ so that:

$$ \begin{align} &\text{max}\left(\left|\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_n}\right|,\ldots,\left|\frac{a_0}{a_n}\right|\right)\cr\cr &\quad = \text{max}\left(\frac{|a_{n-1}|}{|a_n|},\ldots,\frac{|a_0|}{|a_n|}\right)\cr\cr &\quad = \frac{\text{max}(|a_{n-1}|,\ldots,|a_0|)}{|a_n|}\cr\cr &\quad = \frac{M}{|a_n|} \end{align} $$We consider two cases: $|r|\le 1\,$ and $|r| > 1\,.$ In both cases, it must be shown that $\displaystyle\,|r| \le 1 + \frac{M}{|a_n|}\,.$

$|r| \le 1$

Assume $\,|r| \le 1\,.$ Since absolute value is a nonnegative quantity, $\displaystyle\,\frac{M}{|a_n|} \ge 0\,.$ Then, as desired, we have:

$$ \begin{align} |r| &\le 1\cr &\le 1 + \frac{M}{|a_n|} \end{align} $$

$|r| \gt 1$

Assume $\,|r| > 1\,.$ Rewrite (1) as

$$r^n = -\frac{a_0}{a_n} - \frac{a_1}{a_n}r - \cdots - \frac{a_{n-1}}{a_n}r^{n-1}\tag{2}$$Then:

$$ \begin{align} |r^n| \ &= \ \left|-\frac{a_0}{a_n} - \frac{a_1}{a_n}r - \cdots - \frac{a_{n-1}}{a_n}r^{n-1}\right| \cr\cr &\le \ \left|\frac{a_0}{a_n}\right| + \left|\frac{a_1}{a_n}r\right| + \cdots + \left|\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_n}r^{n-1}\right|\cr &\qquad \text{(triangle inequality)}\cr\cr &= \ \frac{|a_0|}{|a_n|} + \frac{|a_1|}{|a_n|}|r| + \cdots + \frac{|a_{n-1}|}{|a_n|}|r^{n-1}|\cr &\qquad \text{(since} \left|\frac{a}{b}\right| = \frac{|a|}{|b|} \text{ and } |ab| = |a|\cdot|b| \text{)}\cr\cr &= \ \frac{1}{|a_n|}\left(|a_0| + |a_1|\cdot|r| + \cdots + |a_{n-1}|\cdot|r^{n-1}|\right)\cr &\qquad \text{(factor out the common factor)} \cr\cr &\le \ \frac{1}{|a_n|}\left(M + M|r| + \cdots + M|r^{n-1}|\right)\cr &\qquad \text{(since $\,M\,$ is the max)}\cr\cr &= \ \frac{1}{|a_n|}\left(M + M|r| + \cdots + M|r|^{n-1}\right)\cr &\qquad \text{(since $\,|r^i| = |r|^i\,$)}\cr\cr &= \ \frac{M}{|a_n|}(1 + |r| + \cdots + |r|^{n-1})\cr &\qquad \text{(factor out $\,M\,$)}\cr\cr &= \ \frac{M}{|a_n|}\left(\frac{|r|^n-1}{|r| - 1}\right)\cr &\qquad \text{(sum the geometric series)} \end{align} $$Thus:

$$ |r^n| \le \frac{M}{|a_n|}\left(\frac{|r|^n-1}{|r| - 1}\right) \tag{3} $$Multiplying or dividing both sides of an inequality by a positive number does not change the direction of the inequality symbol.

Since, by hypothesis, $\,|r| \gt 1\,,$ we have both $\,|r| - 1 \gt 0\,$ and $\,|r|^n \gt 0\,.$

So, dividing both sides of (3) by $\,|r^n| = |r|^n\,$ and multiplying both sides by $\,|r| - 1\,$ gives:

$$ \begin{align} |r| - 1\ &\le \frac{M}{|a_n|}\left(\frac{|r|^n - 1}{|r|^n}\right)\cr\cr &= \frac{M}{|a_n|}\left(1 - \frac{1}{|r|^n}\right)\cr\cr &\lt \frac{M}{|a_n|} \end{align} $$so that:

$$ |r| \lt 1 + \frac{M}{|a_n|} $$Combining both cases ($\,|r| \gt 1\,$ and $\,|r| \le 1\,$), we have the desired result:

$$|r| \le 1 + \frac{M}{|a_n|}$$ QED