Finding the Equation of a Parabola

Finding the Equation of a Parabola

The prior section,

Parabolas:

Definition, Reflectors/

This section covers the reverse direction: going from a graph (or information describing the graph) of a parabola to the equation of the parabola.

This section assumes knowledge of parabolas in standard form, defined as:

- Vertex at the origin

-

One of these two pieces of information:

- Focus on $x$-axis or $y$-axis

- Directrix parallel to $y$-axis or $x$-axis

(These are equivalent, when the vertex is at the origin.)

As shown in the the prior section, such parabolas have equations of the form $\,x^2 = 4py\,$ or $\,y^2 = 4px\,,$ where $\,|p|\,$ gives the distance from the origin to the focus.

Stop and Think: Does the Given Information Uniquely Identify the Parabola?

When you're given information describing a parabola, you should always start by asking yourself: Does the information uniquely describe a parabola? In other words, is there only one parabola that satisfies the given information?

Here are a couple scenarios that do not uniquely define a parabola:

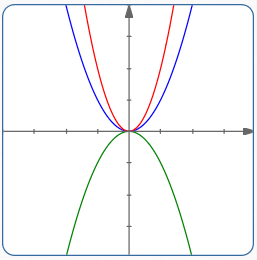

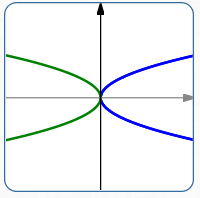

Faulty Question #1: Find ‘the’ Parabola with Vertex at the Origin and Directrix Parallel to the $x$-axis

This is a faulty question; it does not describe a unique parabola, as shown below.

Indeed, there are infinitely many parabolas with vertex at the origin and directrix parallel to the $x$-axis.

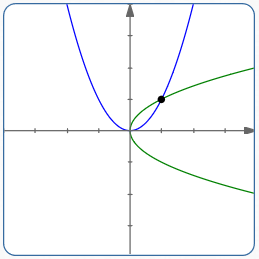

Faulty Question #2: Find ‘the’ Parabola in Standard Form Passing Through the Point $\,(1,1)$

This is a faulty question; it does not describe a unique parabola, as shown below.

There are two parabolas matching the given information: $\,y = x^2\,$ and $\,x = y^2\,.$

What Information Does Uniquely Define a Parabola?

Five Points are Needed to Determine a General Conic

The general conic equation has six unknowns: $A\,,$ $B\,,$ $C\,,$ $D\,,$ $E\,,$ and $F\,$:

$$ \cssId{s32}{Ax^2 + Bxy + Cy^2 + Dx + Ey + F = 0} \qquad \cssId{s33}{(*)} $$One might initially think that six points are needed to solve for these six unknowns. However, only five points are actually needed, as follows:

The Entire Plane, or Nothing

If $\,A = B = C = D = E = F = 0\,,$ then the solution set is the entire plane, since all points $\,(x,y)\,$ satisfy the equation:

$$0x^2 + 0xy + 0y^2 + 0x + 0y + 0 = 0$$To get something other than the entire plane as the solution set, at least one of $\,A\,,$ $\,B\,,$ $\,C\,,$ $\,D\,$ or $\,E\,$ must be nonzero.

(If $\,F\,$ is the only nonzero constant, then the equation is always false.)

Using a Nonzero Coefficient

Dividing both sides of (*) by a nonzero coefficient gives an equivalent equation (an equation with the same graph) that has only five unknown coefficients.

For example, if $\,A\ne 0\,,$ then dividing both sides of (*) by $\,A\,$ gives:

$$\cssId{s44}{x^2 + \frac BAxy + \frac CAy^2 + \frac DAx + \frac EAy + \frac FA = 0}$$or (more simply)

$$\cssId{s46}{x^2 + \hat Bxy + \hat Cy^2 + \hat Dx + \hat Ey + \hat F = 0}$$Five pieces of non-contradictory, non-overlapping information are needed to solve uniquely for these five unknowns.

An example of contradictory information would be: $\,\hat B = 1\,$ and $\,\hat B = 2\,.$ These can't both be true at the same time.

An example of overlapping information would be: $\,\hat B = 1\,$ and $\,\hat B - 1 = 0\,.$ No new information is given with the second equation.

More Requirements to Get ‘Real’ Conics

Note: To get a ‘real’ conic (not a degenerate form or limiting case), no three of the five points can be collinear. Otherwise, you can get things like a line, intersecting lines, or parallel lines; and, you may lose uniqueness.

For example, consider any five points on the $x$-axis.

Any equation of the form $\,Bxy + Cy^2 + Ey = 0\,$ contains the $x$-axis ($\,y = 0\,$) as part of its solution set. (See an example below.)

Thus, there is not a unique ‘conic’ through these points.

Solving For a Conic Through Five Points

Suppose you are given five points $\,(x_1,y_1)\,$ through $\,(x_5,y_5)\,,$ no three of which are collinear. It is highly algebraically intensive to solve (*) for the coefficients $\,A\,$ through $\,F\,.$ (Try it! I suspect you'll throw up your arms in defeat after several pages of calculations!)

If you did complete the calculation, however, you'd find that one of the coefficients can be any real number —then, the other five are determined by it.

What does this mean? What's going on here? To understand, let's look at a simpler and familiar analogous situation:

Looking at a Simple Case: Understanding ‘Degree of Freedom’

As long as $\,A\,$ or $\,B\,$ is nonzero, then the equation $\,Ax + By + C = 0\,$ graphs as a line (possibly vertical or horizontal). (Note: A line is a degenerate case of a parabola, since the discriminant is zero.)

Although there are three unknowns in this equation ($\,A\,,$ $\,B\,$ and $\,C\,$), only two points are needed to determine a line.

What happens if we try to find $\,A\,,$ $\,B\,$ and $\,C\,$ so that the line contains two known distinct points, $\,(x_1,y_1)\,$ and $\,(x_2,y_2)\,$? The approach below solves for both $\,A\,$ and $\,C\,$ in terms of $\,B\,$:

$$ \begin{gather} \cssId{s77}{(1)}\ \cssId{s78}{Ax_1 + By_1 + C = 0}\cr \cssId{s79}{\text{$\,(x_1,y_1)\,$ on the line}}\cr\cr \cssId{s80}{(2)}\ \cssId{s81}{Ax_2 + By_2 + C = 0}\cr \cssId{s82}{\text{$\,(x_2,y_2)\,$ on the line}} \end{gather} $$ $$ \begin{gather} \cssId{s83}{A(x_1-x_2) + B(y_1-y_2) = 0}\cr \cssId{s84}{\text{Use elimination: subtract (2) from (1)}} \end{gather} $$ $$ \cssId{s85}{(3)}\ \cssId{s86}{A = -B\cdot\frac{y_1-y_2}{x_1-x_2} = -B\cdot\frac{y_2-y_1}{x_2-x_1}} $$Solve for $\,A\,$ in terms of $\,B\,,$ assuming $\,x_1 \ne x_2\,.$

Note: if $\,x_1 = x_2\,$ then the line is vertical.

Continuing:

$$\begin{align} \cssId{s91}{C}\ &\cssId{s92}{= -Ax_1 - By_1}\cr &\qquad \cssId{s93}{\text{Solve for $\,C\,$ in (1)}}\cr\cr &\cssId{s94}{= B\cdot\frac{y_2-y_1}{x_2-x_1}x_1 - By_1}\cr &\qquad \cssId{s95}{\text{Use (3) for $\,A\,$}}\cr\cr &\cssId{s96}{= B\left(\frac{y_2-y_1}{x_2-x_1}x_1 - y_1\right)}\cr &\qquad \cssId{s97}{\text{Simplify; this gives $\,C\,$ in terms of $\,B\,$}} \end{align} $$Substitution of the expressions for $\,A\,$ and $\,C\,$ in terms of $\,B\,$ into $\,Ax + By + C = 0\,$ gives:

Equation (4)

So, $\,B\,$ can be any real number.

If $\,B = 0\,,$

then $\,A\,$ and $\,C\,$ are also zero.

In this case, the equation

$\,0x + 0y + 0 = 0\,$ is true for all real numbers $\,x\,$ and $\,y\,.$

For $\,B\ne 0\,$:

Divide both sides of (4) by $\,B\,$

Clear fractions

Factor

Solve for $\,y - y_1$

With $\,m := \frac{y_2-y_1}{x_2-x_1}\,$ (the slope of the line), this is of course the familiar point-slope equation of a line.

For our purposes here, the important understanding is that only two points were needed, not three; and one of the unknowns (for us, $\,B\,$) became a degree of freedom in the equation.

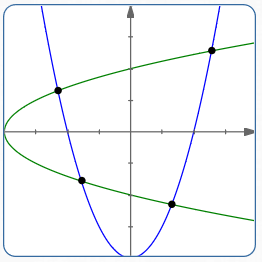

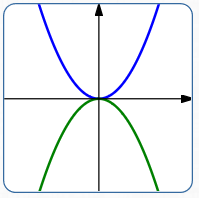

Four Points Aren't Enough to Uniquely Define a General Parabola

Below, the blue parabola ($\,y = x^2 - 4\,$) and the green parabola ($\,x = y^2 - 4\,$) intersect in the four points shown.

An additional point (making a fifth point) is needed to uniquely specify the parabola.

This illustrates that four points are not enough to uniquely define a general parabola. Under certain circumstances, however, we can get away with fewer points. Keep reading!

Only One Point Needed to Determine a Parabola in Standard Form

If a parabola is known to be in standard form ($\,x^2 = 4py\,$ or $\,y^2 = 4px\,$), then only one point is needed to determine the single unknown $\,p\,.$

Example

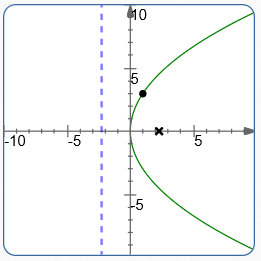

Find the equation of the parabola with vertex at the origin, directrix parallel to the $y$-axis, passing through the point $\,(1,3)\,.$ Find the focus and directrix of the parabola.

Solution

A quick sketch shows that the desired parabola has all $x$-values positive.

Therefore, the parabola must be of the form $\,y^2 = 4px\,.$ Why? Since $\,y^2\,$ is always nonnegative, $\,4px\,$ must also always be nonnegative; this forces all the $x$-values to have the same sign.

Since the point $(1,3)\,$ must satisfy the equation, we have:

$$ \begin{gather} \cssId{s137}{3^2 = 4p(1)}\cr \cssId{s138}{p = \frac 94} \end{gather} $$Thus, the desired equation is $\,y^2 = 4(\frac 94)x\,$; that is, $\,y^2 = 9x\,.$

Since $\,p\,$ gives the $x$-value of the focus, the focus is $\,(\frac 94,0)\,.$

Since the vertex (the origin) is halfway between the focus and directrix, the equation of the directrix is $\,x = -\frac 94\,.$

Finding the Equation of a Parabola: Two Approaches

Problem

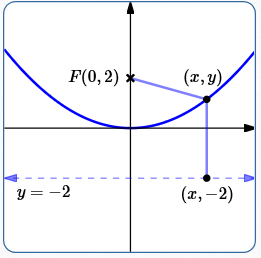

Find the equation of the parabola in standard form with focus $\,(0,2)\,.$

Solutions

Since the equation is in standard form, the vertex is at the origin.

Safest Approach: Use the Definition of Parabola

This approach does not require

memorization/

By definition, a parabola is the set of all points equidistant from the focus and directrix.

Since the vertex is halfway between the focus and directrix, the directrix is the line $\,y = -2\,.$

Let $\,(x,y)\,$ be a typical point on the parabola.

Using the distance formula, the distance from $\,(x,y)\,$ to the focus is:

$$\cssId{s156}{\sqrt{(x-0)^2 + (y-2)^2} = \sqrt{x^2 + (y-2)^2}}$$(The points have the same $x$-value—just compute distance along a line.)

Equating the distances gives:

$$ \begin{gather} \cssId{s160}{\sqrt{x^2 + (y-2)^2} = y+2}\cr\cr \cssId{s161}{x^2 + (y-2)^2 = (y+2)^2}\cr\cr \cssId{s162}{x^2 + y^2 - 4y + 4 = y^2 + 4y + 4}\cr\cr \cssId{s163}{x^2 = 8y} \end{gather} $$Using Knowledge of the Standard Forms

$x^2 = 4py$

(Focus on $y$-axis)

Since $\,x^2\,$ is nonnegative, so is $\,4py\,.$

This forces $\,y\,$ to always have the same sign.

$y^2 = 4px$

(Focus on $x$-axis)

Since $\,y^2\,$ is nonnegative, so is $\,4px\,.$

This forces $\,x\,$ to always have the same sign.

This approach is quicker, but requires knowledge of the standard forms and the significance of $\,p\,$ in these standard forms.

Since the focus is on the $y$-axis, the form is $\,x^2 = 4py\,,$ where $\,p\,$ is the $y$-value of the focus. So, $\,p = 2\,.$

Thus, the equation of the parabola is:

$$\begin{gather} \cssId{s181}{x^2 = 4py}\cr \cssId{s182}{x^2 = 4(2)y}\cr \cssId{s183}{x^2 = 8y} \end{gather} $$Of course, both approaches give the same solution!